The Way From 2 September 1945 to 1999

She said: "I admit, I was fascinated by Adolf Hitler. He was a pleasant boss and a fatherly friend. I deliberately ignored all the warning voices inside me and enjoyed the time by his side, almost until the bitter end. It wasn't what he said, but the way he said things and how he did things."[5]

Encouraged by Hitler, in June 1943, Traudl married Waffen-SS officer Hans Hermann Junge (1914–1944), who had been a valet and orderly to Hitler. Junge died in combat in France in August 1944.[6][7] She worked at Hitler's side in Berlin, the Berghof in Berchtesgaden, at Wolfsschanze in East Prussia, and back again in Berlin in the Führerbunker. Who Knew Imagine...

Berlin, 1945[edit]

In 1945, Junge was with Hitler in Berlin. During Hitler's last days in Berlin, he would regularly eat lunch with his secretaries Junge and Gerda Christian.[8] After the war, Junge recalled Gerda asking Hitler if he would leave Berlin. This was firmly rejected by Hitler.[9] Both women recalled that Hitler in conversation made it clear that his body must not fall into the hands of the Soviets. He would shoot himself.[9] Junge typed Hitler's last private and political will and testament in the Führerbunker the day before his suicide.[10] Junge later wrote that while she was playing with the Goebbels children on 30 April, "Suddenly [...] there is the sound of a shot, so loud, so close, that we all fall silent. It echoes on through all the rooms. 'That was a direct hit,' cried Helmut [Goebbels] with no idea how right he is. The Führer is dead now."

On 1 May, Junge left the Führerbunker with a group led by Waffen-SS general Wilhelm Mohnke. Also in the group were Hitler's personal pilot Hans Baur, chief of Hitler's Reichssicherheitsdienst (RSD) bodyguard Hans Rattenhuber, secretaries Gerda Christian and Else Krüger, Hitler's dietician Constanze Manziarly and Dr. Ernst-Günther Schenck. Junge, Christian and Krüger made it out of Berlin to the River Elbe. The remainder of the group were found by Soviet Red Army troops on 2 May while hiding in a cellar off the Schönhauser Allee. The Soviet troops handed over those who had been in the Führerbunker to SMERSH for interrogation, to reveal what had occurred in the bunker during the closing weeks of the war.[11]

Post-war[edit]

Although Junge had reached the Elbe, she was unable to reach the western Allied lines, and so she went back to Berlin. Getting there about a month after she had left, she had hoped to take a train to the west when they began running again. On 9 July, after living there for about a week under the alias Gerda Alt, she was arrested by two civilian members of the Soviet military administration and was kept in Berlin for interrogation. While in prison, she heard harrowing tales from her Soviet guards about what the German military had done to members of their families in Russia and came to realise that much of what she thought she knew about the war in the east was only what the Nazi propaganda ministry had told the German people, and that the treatment meted out to Germans by the Soviets was a response to what the Germans had done in the Soviet Union.[12]

Junge was held in multiple jails, where she was often interrogated about her role in Hitler's entourage and the events surrounding Hitler's suicide. By December 1945, she had been released from prison but was restricted to the Soviet sector of Berlin. On New Year's Eve 1945, she was admitted to a hospital in the British sector for diphtheria, and remained there for two months. While she was there, her mother was able to secure for her the paperwork required to allow her to move from the British sector in Berlin to Bavaria. Receiving these on 2 February 1946, she travelled from Berlin and across the Soviet occupation zone (which was to become East Germany) to the British zone, and from there south to Bavaria in the American Zone. Junge was held by the Americans for a short time during the first half of 1946, and interrogated about her time in the Führerbunker. She was then freed, and allowed to live in postwar West Germany.[13]

Career[edit]

Junge was born in Preetz in Schleswig-Holstein Province in February 1914. He joined the Schutzstaffel (SS) and in 1934 volunteered for the 1st SS Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. On 1 July 1936, he became a member of the Führerbegleitkommando, which provided security protection for Hitler.[2] In 1940, Junge became a valet and orderly to Hitler and met Traudl Humps, who was Hitler's last private secretary. Junge was considered Hitler's second valet after Heinz Linge.[3] Junge worked as a valet in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin and at Hitler's residence near Berchtesgaden. According to Traudl, although they were called valets, the two men were really managers of Hitler's household. They accompanied him wherever he went and were in charge of Hitler's daily routine; including waking him, providing newspapers and messages, determining the daily menu/meals and wardrobe. Linge and Junge would trade shifts every two days.[4]

Following the encouragement of Hitler, Junge and Humps married on 19 June 1943. On 14 July 1943, he joined the Waffen-SS.[2] About Junge's going to the front, his wife Traudl wrote in her memoirs:[5]

The following year, he died in combat as an SS-Obersturmführer (first lieutenant) in a low flying aircraft attack in Dreux, France. According to Lehmann and Carroll, "Hitler had liked Hans Junge and was so upset by his death that he broke the news to Traudl Junge personally."[1] Traudl stated that Hitler asked her to stay on as his secretary. He promised to "look after" Traudl now that she was a widow.[6]

The Second World War and Its Aftermath

1941–1951

The outbreak of war in Europe substantially changed the way in which the Federal Reserve System was expected to operate as the nation’s central bank in a period during which US participation in the conflict was imminent. The most important challenge for the System was to deal with the possibility of very large fiscal deficits due to increased war expenditures. Even before the period of active US participation in the conflict, the expansion of the defense program and the decision to help finance allies’ purchases of war material from the United States (under the so-called lend-lease program) significantly increased US government financing needs. After the decision to actively participate in the conflict, the US government substantially increased its expenditures, confirming previous expectations. Despite the fact that the Treasury relied more heavily on taxation than in World War I and despite increased tax revenue from the substantial expansion of industrial production, the active participation in the war resulted in a sharp increase in the federal deficit.

Perhaps the most important actions performed by the System during the war were to control government bond prices to promote stable financial markets and (even more critical) to help reduce the interest rates on financing the extraordinarily large fiscal deficits associated with active participation in the war. In 1939, shortly before the beginning of the conflict in Europe, the System made some open-market purchases to influence the yields on short-term government bonds. The goal was to promote stability in short-term funding markets and prevent market disorder in the face of uncertainty at the outset of the war. Once the United States formally entered the conflict, the system made a firm commitment to support government bond prices. In April 1942, the Federal Open Market Committee announced that it would maintain the annual rate on Treasury bills at three-eighths of 1 percent by buying or selling any amount of Treasury bills offered or demanded at that rate. For longer-maturity government securities, the System also established a maximum yield (or a minimum price) by standing ready to buy whatever amount of these securities was necessary to prevent their yields from rising above the maximum yield. Such a commitment to maintain low yields (high prices) of government bills and bonds necessarily resulted in the purchase of a significant volume of government securities, producing a substantial expansion of the System’s balance sheet and, in particular, of the monetary base. Indeed, the monetary base increased by 149 percent from August 1939 to August 1948.

An additional factor contributing to the increase in the monetary base, and as an immediate consequence of the outbreak of war in Europe, was the acceleration of gold inflows as Britain and other allies paid for war materials and other supplies produced domestically by shipping gold to the United States. These two factors resulted in a vigorous expansion of the monetary base and the money supply. As a result, inflation rose significantly during the period. This happened despite price and wage controls and consumer credit controls (and despite an increased willingness of the nonbank public to hold a significant fraction of their wealth in the form of monetary assets as reflected by the marked decline in the velocity of money observed during the war).1

Most economists at the time believed that as soon as the war ended the economy would likely fall into recession and the unemployment rate would rise substantially, partly because of the experience of previous wars (and the previous decade of the Great Depression) and partly because of the widespread Keynesian view that fiscal stimulus was the most effective means of boosting domestic economic activity, and such stimulus was about to decline with the end of the war. This belief, combined with the decision to continue to hold down Treasury financing costs, certainly contributed to the continuation of the government bond support program for much longer than what would be consistent with price stability. The inability of Federal Reserve officials to persuade the Treasury to let the System abandon the government bond support program (in view of other policy considerations such as price stability) clearly demonstrated that the Federal Reserve System was effectively under Treasury control. As economist Allan Meltzer notes in his book, Chairman Marriner Eccles described his work in wartime as “a routine administrative job…[T]he Federal Reserve merely executed Treasury decisions” (Meltzer 2003, 579).

Given its inability to control growth of the monetary base through open-market operations or the discount window, under the constraints of the program to support government bond prices, the System used other tools to try to control private sector spending and curb inflation. The System imposed direct controls on consumer credit (through regulation W) by introducing minimum down payments and maximum maturities on consumer credit extended through installment loans. Because the reallocation of resources to military production restricted the supply of consumer durable goods, the controls imposed on consumer credit aimed to restrict the demand for these goods in an effort to reduce the pressure on prices. Another major action taken during the period was the increase in the reserve requirements of commercial banks in 1941. However, this measure, which was intended to restrain credit growth and the expansion of bank liabilities, had only a minor effect on the money supply and the trend in the price level.

The end of the war did not mean that the System was automatically freed from Treasury influence. Six years would go by before monetary policy was revived as a major instrument to influence aggregate spending and prices. In March 1951, the System’s policy independence from the Treasury was accomplished with the formal agreement between the Treasury and the System known as the Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord.

The Federal Reserve's Role During WWII

1941–1945

The Great Depression strained societies around the globe. The economic catastrophe produced political tensions that grew throughout the 1930s. World War II was a result. In September 1939, Germany’s invasion of Poland triggered war among the principal European powers. In December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. The American “arsenal of democracy” joined the Allied nations, including Britain, France, China, the Soviet Union, and numerous others, in the fight against the Axis alliance. The Allied counteroffensive began in 1942. The Axis surrendered in 1945.

When the United States entered the war, the Board of Governors issued a statement indicating that the Federal Reserve System was “. . . prepared to use its powers to assure at all times an ample supply of funds for financing the war effort” (Board of Governors 1943, 2). Financing the war was the focus of the Federal Reserve’s wartime mission. This mission differed from the mission of the System before and after the war.

Finance formed a foundation for the war effort. Before the war, America’s military was small, and its weapons were obsolescent. The military needed to purchase thousands of ships, tens of thousands of airplanes, hundreds of thousands of vehicles, millions of guns, and hundreds of millions of rounds of ammunition. The military needed to recruit, train, and deploy millions of soldiers to theaters of action on six continents. Accomplishing these tasks entailed paying entrepreneurs, inventors, and firms so that they, in turn, could purchase supplies, pay workers, and produce the weapons with which America’s soldiers and sailors would defeat its enemies. Military expenditures rose from a few hundred million a year before the war to $85 billion in 1943 and $91 billion in 1944.1

Plans for financing the war were devised by the Treasury and the Federal Reserve. These organizations met frequently to determine how to finance the war and organize machinery for marketing United States government securities.

The plan called for financing the war to the greatest extent possible through taxation and domestic borrowing.2 Paying for the war through levies on current incomes would minimize inflationary pressures, promote economic expansion during the war, and promote economic stability when peace returned.

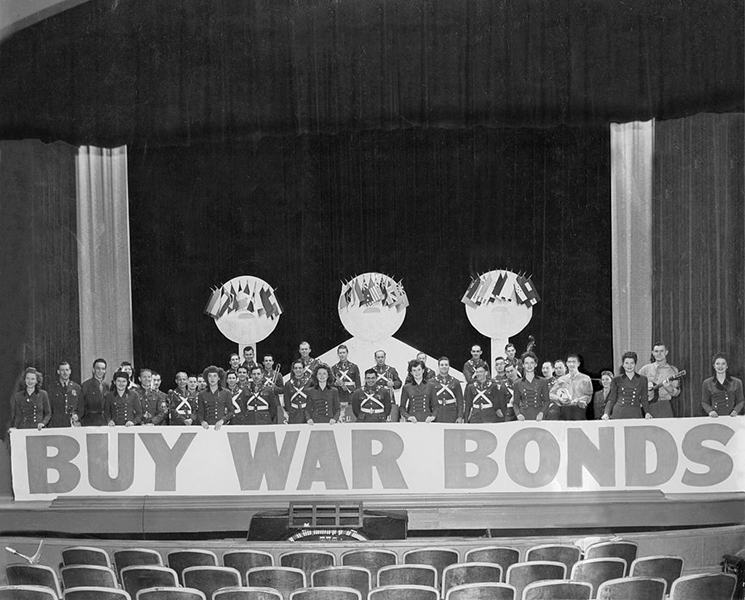

To direct the savings of American citizens into the war effort, the Treasury and Federal Reserve marketed a range of securities that would fit the needs of all classes of investors, from small savers who wished to invest for the duration of the war to large corporations with temporarily idle funds. To distribute these securities, the twelve Federal Reserve Banks organized Victory Fund committees and established plans to market war bonds in cooperation with commercial banks, businesses, and volunteers.

To keep the costs of the war reasonable, the Treasury asked the Federal Reserve to peg interest rates at low levels. The Reserve Banks agreed to purchase Treasury bills at an interest rate of three-eighths of a percent per year, substantially below the typical peacetime rate of 2 to 4 percent. The interest-rate peg became effective in July 1942 and lasted through June 1947. The Reserve Banks reduced their discount rate to 1 percent and created a preferential rate of one-half percent for loans secured by short-term government obligations, substantially below the 3 to 7 percent that had been common during the 1920s. All of the Reserve Banks implemented these rates in the spring of 1942. The rates remained in effect until January 1948.3

The Federal Reserve focused on supporting war financing while minimizing inflationary consequences. Inflation was a fear because wartime policies increased incomes, employment, and the money supply, while restricting the available supply of consumer goods. When more money chases fewer goods, prices typically rise. To prevent price increases from undermining the war effort, the government instituted an array of programs. These included regulations on the prices of goods and wages of workers and a rationing program for scarce commodities and consumer durables. The Federal Reserve aided these efforts by regulating consumer credit. The Board’s Regulation W imposed large down payments and short maturities on loans to purchase a wide range of consumer durables. Installment loans were limited to twelve months. Single-payment loans were limited to ninety days.

To enable the Federal Reserve to accomplish its wartime tasks, the Board of Governors asked Congress to amend the Federal Reserve Act. One amendment enabled the Board to change reserve requirements in banks in New York City and Chicago, known as central reserve cities, without changing requirements for other banks. A second amendment authorized the System to purchase government securities directly from the Treasury. A third amendment exempted war loan deposits from reserve requirements for the duration of the emergency.

The president also issued a series of executive orders that shaped the System’s wartime roles. Executive Order 9112, issued on March 26, 1942, established a program of guaranteed loans to industry for war production. Executive Order 9336, issued on April 24, 1943, expanded the scope of the program. For this program, the Board devised the general policies, after consulting with the Reserve Banks as well as the War Department, Navy Department, Maritime Commission, Office of Lend-Lease Administration, and the War Shipping Administration. The Reserve Banks and branches acted as fiscal agents for those organizations. The banks and branches analyzed the financial integrity of loan applicants, determined the types of financing best suited to meet the borrowers’ needs, prepared the necessary documents, and, for all loans under $100,000 (i.e., more than half of all loans), expedited the process by handling the loan on the spot. This swift, decentralized procedure expedited operations for the government and loan applicant, speeding the rate of industrial expansion.

The twelve Federal Reserve banks and twenty-four branches played prominent roles in these efforts, and their work on behalf of the government in connection expanded throughout the war. In 1939, the Reserve Banks employed about 11,000 individuals. In 1943 and 1944, employment in Reserve Banks hit a wartime peak of over 24,000. The War Manpower Commission declared Reserve Banks’ efforts to be essential to the war effort. So, Reserve Bank employees were not subject to the draft, although hundreds of Federal Reserve employees volunteered for military service.

About half the System’s total personnel were engaged in fiscal agency activities. The majority of those employees were assigned to savings bond operations. The bond drives entailed considerable work by employees and officers of the reserve banks, including the bank presidents.

The handling of war savings bonds was the largest single operation performed by the Federal Reserve Banks. The Federal Reserve cooperated fully with the Treasury in the task of organizing and administering the war loan drives. The work included assistance in the preparation and distribution of publicity materials such as manuals and letters of instruction to workers in the drives, printing and distribution of subscription blanks, and tabulation of detailed reports on the results of the drives.

The Reserve Banks issued savings bonds directly to the public, and, as fiscal agents, maintained consignment accounts with thousands of banks and other agents who issued savings bonds. The Reserve Banks coordinated their activities as well as the activities of thousands of volunteers and companies who helped to market the bonds. The majority of the bonds issued were in small denominations ($25 or less), which explains the tremendous amount of work involved. As the bonds were sold, reports and remittances were received as well as the bond stubs, which indicated who purchased each bond. The stubs were consolidated with those representing bonds issued directly by Reserve Banks, and then tabulated and forwarded to the Treasury. The Reserve Banks were the sole redemption agency for the bonds outside of Washington, DC. Many Reserve Banks and branches set up separate savings bond redemption centers outside their regular banking quarters.

The Federal Reserve Board and Banks marketed war bonds to their own employees. Each entity tracked total sales and publicized it in the workplace. Employees of the New York Fed, for example, purchased over $87,000 worth of bonds in April 1943, enabling the army to purchase a 105mm howitzer and a P-51 Mustang fighter plane. In August 1944, the New York Fed received a letter and photograph of the plane, named the “N.Y. Federalist,” which was based in England and flew operations over France and Germany

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago rendered a special service to the Treasury in handling cases of reissued savings bonds that could not be settled without clearance from the Treasury. The Chicago Fed handled all of these cases, from all parts of the country, whether submitted through a reserve bank or directly through the Treasury. The Chicago Fed also provided a safekeeping service for all savings bonds purchased by personnel of the War Department. The Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland provided safekeeping services for savings bonds purchased by naval personnel.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York carried out operations of the Exchange Stabilization Fund in accordance with authorizations and instructions from the Treasury. These operations included the purchase and sale of gold and foreign exchange and the maintenance of accounts for various foreign central banks and foreign governments in connection with relations between the United States and its allies overseas. The NY Fed engaged in foreign transactions on an extensive scale. It held gold and dollar accounts for fifty-nine foreign nations. It became increasingly involved in handling official remittances from the United States to foreign countries, particularly in connection with the maintenance abroad of American armed forces.

All of the Reserve Banks acted as agents for the Treasury’s foreign funds control operations. The goal was to facilitate legitimate transactions while erecting barriers against Axis manipulation of dollar assets and Axis access to international markets. The Reserve Banks processed applications for licenses and reports of transactions.

In sum, the Federal Reserve played important roles during World War II. The Fed helped to finance the war, fund our allies, embargo our enemies, stabilize the economy, and plan the postwar return to peacetime activities.

While the Fed helped on the home front, thousands of Federal Reserve employees and millions of Americans enlisted in the armed forces; over 400,000 of those who served, including scores of Fed employees, gave their lives for their country. Men from the Federal Reserve fought and died in the hedgerows in Normandy, the Bulge in Belgium, the mountains of Italy, and the beaches of the Pacific. In an oral history interview, a career employee of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas recounted her most memorable day at work: December 8, 1941. She and her coworkers listened to the radio as President Roosevelt described the attack on Pearl Harbor and announced Congress’s declaration of war against Japan. Afterward, silently, one after another, seven men rose from their desks and left the building to volunteer for service.

Financing, World War II

FINANCING, WORLD WAR II

World War II was the most expensive war in American history, exceeding all other conflicts in economic impact. Nearly forty million Americans paid income taxes for the first time, and an elaborate price control system touched the life of every consumer. To sell war bonds, the U.S. government made direct and frequent contact with more than 90 percent of the American population. The U.S. government financed a massive expansion of the nation's defense industry, so that by 1945 the government owned billions of dollars worth of factories and machinery.

planning

During the two years before the United States entered the war, the enormity of America's financial burden became apparent. At the war's peak, federal expenditures were twelve times greater than in the last peacetime year. President Franklin D. Roosevelt hoped to pay for half the cost of the war, or more, out of current income, but collecting such a colossal sum was a daunting task. Roosevelt was determined not to rely too heavily on loans, but borrowing was inevitable.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor angered, frightened, and unified the nation, but although the public was eager to contribute to the war effort, Roosevelt's economic policies still faced difficulties. Some members of Congress disliked Roosevelt's political agenda in any form, and others were reluctant to face reelection after raising taxes. Roosevelt's greatest problem, however, was how to tap into the middle and lower income levels. Rampant consumer spending had led to large price increases during World War I.

broadening the income tax

Tax experts generally agreed that the income tax was the fairest, most effective way to draw upon the spending power of the middle class. Some leaders preferred a national sales tax, but against the opposition of the president the idea went nowhere. The treasury proposed a tax on individual spending, but the plan's complexity doomed it as well. The income tax, formerly the domain of the wealthy alone, would have to be broadened to apply to Americans of average income.

In 1941 and again in 1942, Congress lowered income tax exemptions and adopted steeply graduated rates. These ranged from 13 percent on the first $2,000 of individual income up to 82 percent on income above $200,000. Gift and estate taxes were also broadened, and a graduated tax on excess corporate incomes added to the progressive nature of the tax structure, which became the highest in American history. Excise taxes on alcoholic beverages, tobacco, and gasoline rose dramatically as well.

Because the taxpaying public perceived the income tax as a levy that should apply only to the wealthy, the government feared noncompliance. "Suppose we have to go out and try to arrest five million people?" Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau said. To keep this from happening, and because most Americans were ignorant of the procedure for filling out an income tax form, the treasury devised a clever and effective public relations campaign, such as The New Spirit. Responding to this and other appeals, most Americans made a good-faith effort to pay their taxes.

collection at the source

The income tax was a bountiful source of income, but it had one great disadvantage: Before 1943, it was paid only quarterly. Since defense spending was producing huge daily deficits, tax collection had to be accelerated. The answer was to put the income tax on a pay-as-you-go basis-in other words, to withhold a sum for tax purposes from every paycheck, with a small reconciliation payment (or refund) due at year's end. The problem with this scheme was that, in the year the change was made, taxpayers would have to pay their taxes twice, once for the previous year and again for the current year. Although this was Roosevelt's preference, many argued that it would be an unfair burden. They demanded that in return for accepting the pay-as-you-go system taxpayers be excused from making the prior year's annual payment. Against Roosevelt's wishes, Congress agreed to forgive three-fourths of a year's tax payments, a compromise that transferred the payment to the shoulders of postwar taxpayers.

war bonds

The World War I system of marketing war bonds through propaganda posters, pamphlets, and patriotic rallies was resurrected and expanded in World War II. Between the wars, most American families had acquired radios, which simplified the government's work in appealing for funds. Patriotic pleas, presented by performers such as the cowboy star Roy Rogers, flooded the airwaves. The treasury even presented its own variety show, The Treasury Star Parade, to coax the public to purchase war bonds regularly.

To reach people with the lowest incomes, the treasury made the purchase of bonds much easier. Bonds sold for $50 in World War I, but in WWII the treasury sold stamps—which could be used to buy bonds—in denominations ranging from $0.10 to $5. The Series E bond, which sold for $18.75 but could be redeemed for $25 in ten years, was the most popular. (Sixty years later, a modified version, the Series EE, was still available.)

wage and price controls

Taxes and war bonds diverted consumer spending, but if wages rose significantly consumers might bid against the government for scarce resources. To prevent this, and to preserve equity in the economy, in April 1942 the government instituted a system of wage and price controls. Wages and retail prices were restricted according to a fixed schedule, and Roosevelt limited the compensation of business executives to $25,000 after taxes.

Initially, the price control system worked well. But as rising production demands placed pressure on scarce resources, flaws began to appear. The first was in the price of steel, which was vital to warships and tanks. Controlling the price of gasoline was an even thornier problem, and a shortage of rubber arose due to the Japanese capture of Southeast Asia. Driving was restricted: the government rationed gasoline, imposed a nationwide speed limit, and attempted to prohibit all motoring for pleasure. No wartime measure was more unpopular or difficult to enforce. A lively market for illegal, or black market gasoline developed, but in spite of the black market inflation during World War II was comparatively modest. Whereas the cost of living doubled during World War I, inflation was held to about 28 percent during World War II.

foreign loans

The Roosevelt administration was skittish about making loans to foreign governments. Many Americans believed that during the 1930s America's World War I allies had improperly suspended payments on their debts, and they were leery of lending money again. To address this difficulty, Roosevelt proposed to lend only military equipment, all of which was to be returned after the war. The lend-lease program adroitly avoided the issue of whether debts would be repaid after the war.

THE NEW SPIRIT

More than two-thirds of the American population attended at least one movie each week during World War II, offering an ideal opportunity for a patriotic appeal. Early in 1942, the treasury department asked the Disney studio to produce The New Spirit, a short animated film featuring Donald Duck paying his income taxes. Arming himself with an aspirin bottle and aided by an animated ink bottle and pen, Donald finds that filling out his tax form is surprisingly painless. With three deductions for his dependents Huey, Dewey, and Louie, Donald's tax is only $13 on his actor's income of $2,501. More than thirty-two million people saw the film, which was shown on twelve thousand screens, and 37 percent of the moviegoers reported that it had a positive effect on their willingness to pay their taxes.

defense plants

In wartime, the United States had traditionally relied on converting existing factories to defense production. In World War II, to encourage plant conversion and expansion, the government again offered liberal tax incentives and paid attractive, high-incentive prices. In return, contractors agreed to a system of price renegotiation that was intended to prevent swollen profits. But the existing manufacturing facilities could not produce the immense

quantities of planes and tanks that World War II required. New plants had to be built, and only the government could supply the capital necessary to finance them.

In 1940, Congress created the Defense Plant Corporation, which could build an entire factory and then lease it to a contractor. This firm financed about 30 percent of the new facilities that were built during the war, and the government came to own major portions of the synthetic rubber, aircraft, magnesium, and aluminum businesses. By the war's end, the government had invested billions of dollars in factories and machinery and owned about one-sixth of the nation's industrial capacity. Since there was little postwar need for many of these facilities, the government sold them to the highest bidder in an auction popularly known as Uncle Sam's garage sale. Some contractors realized excellent bargains, purchasing equipment or even whole factories at a fraction of their cost.

When the war ended, America's financial strength was unrivaled. The United States possessed the most powerful revenue source ever devised, the mass-collected personal income tax. It had claim to billions of dollars in military equipment that was in the possession of its wartime allies, and it owned a significant portion of the nation's manufacturing capacity. It had successfully limited the wages and salaries of the nation's workers and managers, and it had restricted the prices of nearly all consumer products. About 40 percent of the cost of World War II was financed out of current revenue, an improvement on the Civil War (28 percent) and World War I (36 percent). The nation could be rightfully proud of a job well done.

TAXING THE TAXABLE

When a Tax Break Is Actually a Tax Penalty

The curious case of the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance.

When is a tax break actually a tax penalty? When it's the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance.

That's what Michael Cannon, Cato Institute's director of health policy studies, convincingly argues in his recent paper, End the Tax Exclusion for Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance. His paper is a compact lesson in the ways that some supposed tax breaks can effectively function as tax penalties, not only distorting markets, but invisibly penalizing people for their choices. And it's a reminder of the ways that seemingly minor, offhanded policy decisions, made with little thought to long-term consequences, can exert a haunting influence long after they are made.

The tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance is exactly what it sounds like: a carve-out for health coverage offered through the workplace.

If an employer were to pay an employee $10,000 in cash, that money would be taxed at an average rate of about 33 percent, meaning that the employee would only see about $6,666. If, on the other hand, the employer were to compensate an employee with $10,000 in health insurance purchased by the employer, the value of that plan would be exempt from federal income and payroll taxes. The employee would receive the full value of the plan.

This makes workplace health benefits more valuable, on a dollar-for-dollar basis, than cash compensation, and thus incentivizes purchasing more of it than if the tax treatment of cash and health benefits were equal. It acts as a subsidy.

In his paper, Cannon allows that "from an accounting perspective, the exclusion is a tax break: It reduces the tax liability of workers who enroll in employer-sponsored coverage."

But he argues that, in practical terms, this tax break actually acts as a stealth penalty on workers who want to make their own health insurance choices. Typically even a generous employer only offers a handful of health plans, and those plans are unlikely to take the exact form an employee would otherwise choose on his or her own. If an employee wants to purchase any other plan, however, he or she would have to do it with money first received—and taxed—as cash compensation. Thanks to taxation, it would be worth a lot less. Thus the tax exclusion acts as a tax penalty on any employee who wants to choose their own health insurance.

The existence of a penalty implies a kind of coercion. Recall that when the Supreme Court blessed Obamacare's individual mandate to purchase health insurance as constitutional, it was by construing the mandate as a tax penalty for not purchasing health insurance rather than a direct economic command. That ruling highlighted the thin line between tax penalties and coercive mandates; Cannon's argument draws out the logical linkage even further: So while the tax exclusion for employer-provided insurance might look, on paper, like a tax break, viewed from an economic perspective it is functionally similar to a mandate.

And yet it was never explicitly intended as such. Rather, the exclusion stems from a complicated series of bureaucratic decisions dating back more than 100 years. Following the creation of the income tax, Treasury officials had to decide how to treat health insurance that sometimes included wage payments for sick time, a minor issue at most since few people had health coverage at the time.

In 1942, however, with World War II raging, the federal government froze wages as part of the war effort, but ruled that pension and health benefits were exempt. That meant that employers had to rely heavily on such benefits to attract talent. Not surprisingly, employer-provided health insurance became much more common. A little more than a decade later, Congress formally codified the exemption. By the 1970s, the large majority of American workers obtained health insurance through their employers.

So what seemed at first to be a minor bureaucratic decision of little consequence eventually became the primary vehicle by which Americans received private health coverage, and, consequently, a huge determinant of American health care spending.

By Cannon's calculation, the tax exclusion effectively removes control of nearly $1 trillion worth of compensation from workers—the total value of the employer share of workplace health coverage. His paper is a call to end the coercive policy that created this situation and replace it with a system of large health savings accounts that would let workers control that money and be free to make their own health insurance choices.

The tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance is the original sin of the U.S. health care system. To unwind its effects, we must first see it clearly for what it is: not a harmless tax break, but a coercive policy mechanism that undermines a core economic freedom.

Comments

Post a Comment

No Comment