Epistemology

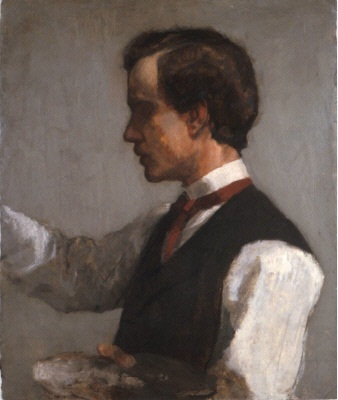

Portrait of William James by John La Farge, c. 1859

James defined true beliefs as those that prove useful to the believer. His pragmatic theory of truth was a synthesis of correspondence theory of truth and coherence theory of truth, with an added dimension. Truth is verifiable to the extent that thoughts and statements correspond with actual things, as well as the extent to which they "hang together," or cohere, as pieces of a puzzle might fit together; these are in turn verified by the observed results of the application of an idea to actual practice.

The most ancient parts of truth … also once were plastic. They also were called true for human reasons. They also mediated between still earlier truths and what in those days were novel observations. Purely objective truth, truth in whose establishment the function of giving human satisfaction in marrying previous parts of experience with newer parts played no role whatsoever, is nowhere to be found. The reasons why we call things true is the reason why they are true, for 'to be true' means only to perform this marriage-function.

— "Pragmatism's Conception of Truth," Pragmatism (1907), p. 83.

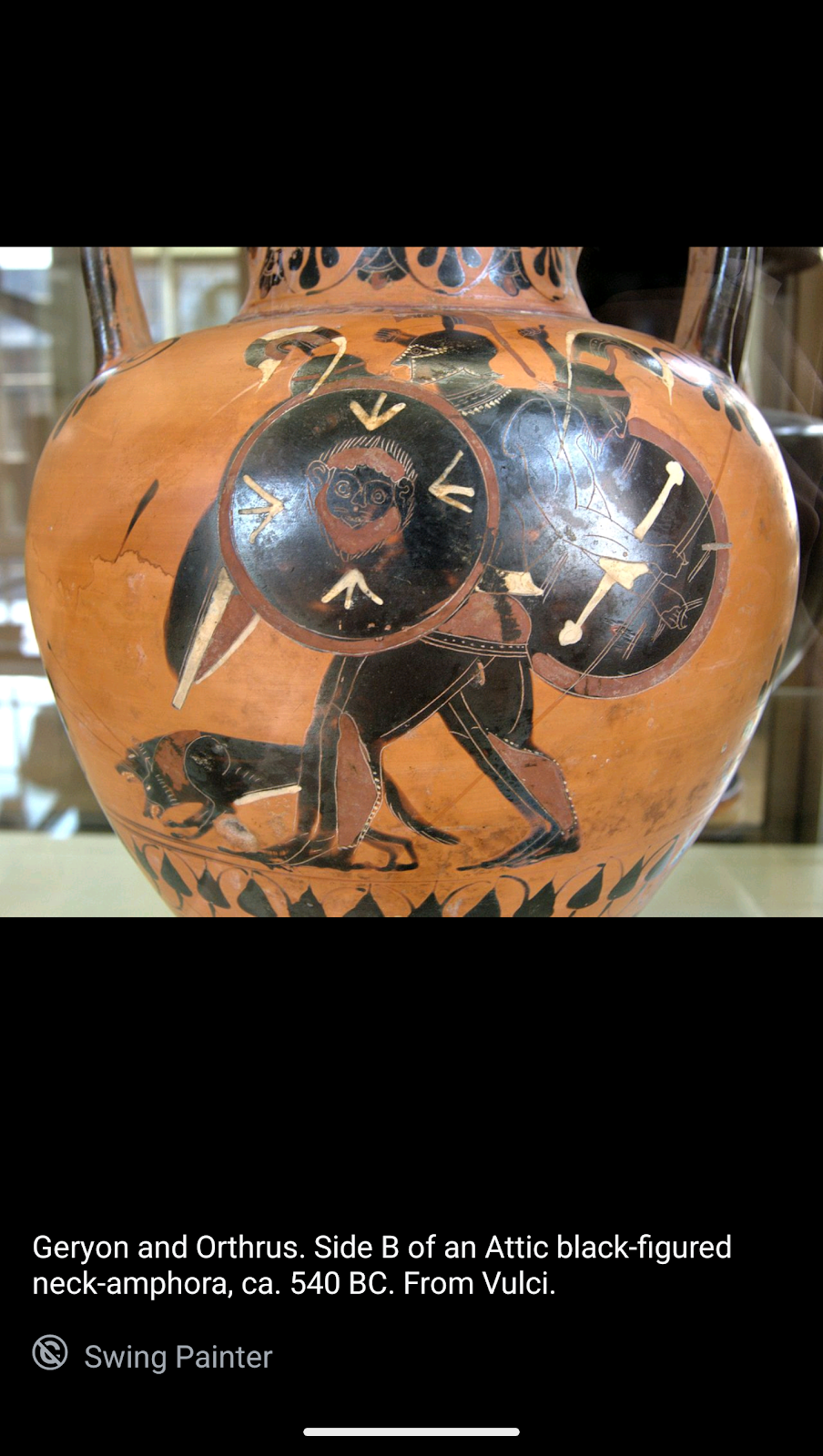

According to Hesiod Geryon had one body and three heads, whereas the tradition followed by Aeschylus gave him three bodies. A lost description by Stesichoros said that he has six hands and six feet and is winged; there are some mid-6th century BC Chalcidian vases portraying Geryon as winged.

Some accounts state that he had six legs

as well while others state that the three bodies were joined to one pair of legs. Apart from these bizarre features, his appearance was that of a warrior. He owned a two-headed hound named Orthrus, which was the brother of Cerberus, and a herd of magnificent red cattle that were guarded by Orthrus, and a herder Eurytion, son of Erytheia.

Or thrust

Or thus

Or the other us

The magnetic 🧲 roundness of all magnetic rounded fields is printed on red stone in black ink lined with white lines rounded where round rounds up pointed where round points down suffering the slings and arrows of poor misfortune never defeated always down for another round followed by a faithful dog dealing with the diagonal as dogs do do

Depictions of Orthrus in art are rare, and always in connection with the theft of Geryon's cattle by Heracles. He is usually shown dead or dying, sometimes pierced by one or more arrows.

The earliest depiction of Orthrus is found on a late seventh-century bronze horse pectoral from Samos (Samos B2518). It shows a two-headed Orthrus, with an arrow protruding from one of his heads, crouching at the feet, and in front of Geryon. Orthrus is facing Heracles, who stands to the left, wearing his characteristic lion-skin, fighting Geryon to the right.

A red-figure cup by Euphronios from Vulci c. 550–500 BC (Munich 2620) shows a two-headed Orthrus lying belly-up, with an arrow piercing his chest, and his snake tail still writhing behind him. Heracles is on the left, wearing his lion-skin, fighting a three-bodied Geryon to the right. An Attic black-figure neck amphora, by the Swing Painter c. 550–500 BC (Cab. Med. 223), shows a two-headed Orthrus, at the feet of a three-bodied Geryon, with two arrows protruding through one of his heads, and a dog tail.

According to Apollodorus, Orthrus had two heads; however, in art, the number varies. As in the Samos pectoral, Euphronios' cup, and the Swing Painter's, amphora, Orthrus is usually depicted with two heads, although, from the mid sixth century, he is sometimes depicted with only one head, while one early fifth century BC Cypriot stone relief gives him three heads, á la Cerberus.

The Euphronios cup, and the stone relief depict Orthrus, like Cerberus, with a snake tail, though usually he is shown with a dog tail, as in the Swing Painter's amphora.

Comments

Post a Comment

No Comment