Stars of the shew

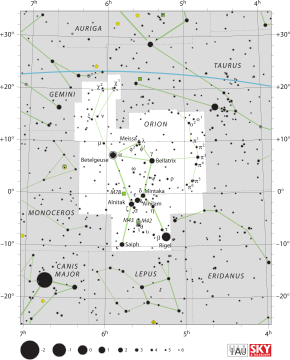

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Ori |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Orionis |

| Pronunciation | /ɒˈraɪ.ən/ |

| Symbolism | Orion, the Hunter |

| Right ascension | 5h |

| Declination | +5° |

| Quadrant | NQ1 |

| Area | 594 sq. deg. (26th) |

| Main stars | 7 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 81 |

| Stars with planets | 10 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 8 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 8 |

| Brightest star | Rigel (β Ori) (0.12m) |

| Messier objects | 3 |

| Meteor showers | Orionids Chi Orionids |

| Bordering constellations | Gemini Taurus Eridanus Lepus Monoceros |

| Visible at latitudes between +85° and −75°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of January.  | |

Sirius A is about twice as massive as the Sun (M☉) and has an absolute visual magnitude of +1.43. It is 25 times as luminous as the Sun,[13] but has a significantly lower luminosity than other bright stars such as Canopus, Betelgeuse, or Rigel. The system is between 200 and 300 million years old.[13] It was originally composed of two bright bluish stars. The initially more massive of these, Sirius B, consumed its hydrogen fuel and became a red giant before shedding its outer layers and collapsing into its current state as a white dwarf around 120 million years ago.[13]

Sirius is colloquially known as the "Dog Star", reflecting its prominence in its constellation, Canis Major (the Greater Dog).[19] The heliacal rising of Sirius marked the flooding of the Nile in Ancient Egypt and the "dog days" of summer for the ancient Greeks, while to the Polynesians, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, the star marked winter and was an important reference for their navigation around the Pacific Ocean.

Distance[edit]

In his 1698 book, Cosmotheoros, Christiaan Huygens estimated the distance to Sirius at 27,664 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun (about 0.437 light-year, translating to a parallax of roughly 7.5 arcseconds).[42] There were several unsuccessful attempts to measure the parallax of Sirius: by Jacques Cassini (6 seconds); by some astronomers (including Nevil Maskelyne)[43] using Lacaille's observations made at the Cape of Good Hope (4 seconds); by Piazzi (the same amount); using Lacaille's observations made at Paris, more numerous and certain than those made at the Cape (no sensible parallax); by Bessel (no sensible parallax).[44]

Scottish astronomer Thomas Henderson used his observations made in 1832–1833 and South African astronomer Thomas Maclear's observations made in 1836–1837, to determine that the value of the parallax was 0.23 arcsecond, and error of the parallax was estimated not to exceed a quarter of a second, or as Henderson wrote in 1839, "On the whole we may conclude that the parallax of Sirius is not greater than half a second in space; and that it is probably much less."[45] Astronomers adopted a value of 0.25 arcsecond for much of the 19th century.[46] It is now known to have a parallax of nearly 0.4 arcseconds.

The Hipparcos parallax for Sirius is only accurate to about ±0.04 light years, giving a distance of 8.6 light years.[9] Sirius B is generally assumed to be at the same distance. Sirius B has a Gaia Data Release 3 parallax with a much smaller statistical margin of error, giving a distance of 8.709±0.005 light years, but it is flagged as having a very large value for astrometric excess noise, which indicates that the parallax value may be unreliable.[11]

Sopdu (also rendered Septu or Sopedu) was a god of the sky and of eastern border regions in the religion of Ancient Egypt.[1] He was Khensit's husband.

As a sky god, Sopdu was connected with the god Sah, the personification of the constellation Orion, and the goddess Sopdet, representing the star Sirius. According to the Pyramid Texts, Horus-Sopdu, a combination of Sopdu and the greater sky god Horus, is the offspring of Osiris-Sah and Isis-Sopdet.[1]

Voiceless palatal fricative

| Voiceless palatal fricative | ||

|---|---|---|

| ç | ||

| IPA Number | 138 | |

| Audio sample | ||

| Encoding | ||

| Entity (decimal) | ç | |

| Unicode (hex) | U+00E7 | |

| X-SAMPA | C | |

| Braille | ||

| ||

| Voiceless palatal approximant | |

|---|---|

| j̊ | |

| IPA Number | 153 402A |

| Encoding | |

| Entity (decimal) | j̊ |

| Unicode (hex) | U+006A U+030A |

| X-SAMPA | j_0 |

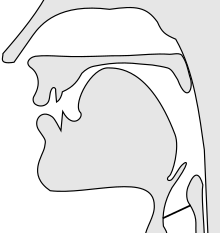

The voiceless palatal fricative is a type of consonantal sound used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ç⟩, and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is C. It is the non-sibilant equivalent of the voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative.

The symbol ç is the letter c with a cedilla (◌̧), as used to spell French and Portuguese words such as façade and ação. However, the sound represented by the symbol ç in French and Portuguese orthography is not a voiceless palatal fricative; the cedilla, instead, changes the usual /k/, the voiceless velar plosive, when ⟨c⟩ is employed before ⟨a⟩ or ⟨o⟩, to /s/, the voiceless alveolar fricative.

Palatal fricatives are relatively rare phonemes, and only 5% of the world's languages have /ç/ as a phoneme.[1] The sound further occurs as an allophone of /x/ (e.g. in German or Greek), or, in other languages, of /h/ in the vicinity of front vowels.

There is also the voiceless post-palatal fricative[2] in some languages, which is articulated slightly farther back compared with the place of articulation of the prototypical voiceless palatal fricative, though not as back as the prototypical voiceless velar fricative. The International Phonetic Alphabet does not have a separate symbol for that sound, though it can be transcribed as ⟨ç̠⟩, ⟨ç˗⟩ (both symbols denote a retracted ⟨ç⟩) or ⟨x̟⟩ (advanced ⟨x⟩). The equivalent X-SAMPA symbols are C_- and x_+, respectively.

Especially in broad transcription, the voiceless post-palatal fricative may be transcribed as a palatalized voiceless velar fricative (⟨xʲ⟩ in the IPA, x' or x_j in X-SAMPA).

Some scholars also posit the voiceless palatal approximant distinct from the fricative, found in a few spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ j̊ ⟩, the voiceless homologue of the voiced palatal approximant.

The palatal approximant can in many cases be considered the semivocalic equivalent of the voiceless variant of the close front unrounded vowel [i̥]. The sound is essentially an Australian English ⟨y⟩ (as in year) pronounced strictly without vibration of the vocal cords.

It is found as a phoneme in Jalapa Mazatec and Washo as well as in Kildin Sami.

Features[edit]

Features of the voiceless palatal fricative:

- Its manner of articulation is fricative, which means it is produced by constricting air flow through a narrow channel at the place of articulation, causing turbulence.

- Its place of articulation is palatal, which means it is articulated with the middle or back part of the tongue raised to the hard palate. The otherwise identical post-palatal variant is articulated slightly behind the hard palate, making it sound slightly closer to the velar [x].

- Its phonation is voiceless, which means it is produced without vibrations of the vocal cords. In some languages the vocal cords are actively separated, so it is always voiceless; in others the cords are lax, so that it may take on the voicing of adjacent sounds.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- The airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles, as in most sounds.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment

No Comment