Bet Here Alph to μ

Alpha /ˈælfə/[1] (uppercase Α, lowercase α)[a] is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter aleph ![]() , which is the West Semitic word for "ox".[2] Letters that arose from alpha include the Latin letter A and the Cyrillic letter А.

, which is the West Semitic word for "ox".[2] Letters that arose from alpha include the Latin letter A and the Cyrillic letter А.

In Ancient Greek, alpha was pronounced [a] and could be either phonemically long ([aː]) or short ([a]). Where there is ambiguity, long and short alpha are sometimes written with a macron and breve today: Ᾱᾱ, Ᾰᾰ.

- ὥρα = ὥρᾱ hōrā Greek pronunciation: [hɔ́ːraː] "a time"

- γλῶσσα = γλῶσσᾰ glôssa Greek pronunciation: [ɡlɔ̂ːssa] "tongue"

In Modern Greek, vowel length has been lost, and all instances of alpha simply represent the open front unrounded vowel IPA: [a].

In the polytonic orthography of Greek, alpha, like other vowel letters, can occur with several diacritic marks: any of three accent symbols (ά, ὰ, ᾶ), and either of two breathing marks (ἁ, ἀ), as well as combinations of these. It can also combine with the iota subscript (ᾳ).

Beta (UK: /ˈbiːtə/, US: /ˈbeɪtə/; uppercase Β, lowercase β, or cursive ϐ; Ancient Greek: βῆτα, romanized: bē̂ta or Greek: βήτα, romanized: víta) is the second letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 2. In Ancient Greek, beta represented the voiced bilabial plosive IPA: [b]. In Modern Greek, it represents the voiced labiodental fricative IPA: [v] while IPA: [b] in borrowed words is instead commonly transcribed as μπ.[1][2] Letters that arose from beta include the Roman letter ⟨B⟩ and the Cyrillic letters ⟨Б⟩ and ⟨В⟩.

Like the names of most other Greek letters, the name of beta was adopted from the acrophonic name of the corresponding letter in Phoenician, which was the common Semitic word *bayt ('house', compare Arabic: بيت bayt and Hebrew: בית báyit). In Greek, the name was βῆτα bêta, pronounced [bɛ̂ːta] in Ancient Greek. It is spelled βήτα in modern monotonic orthography and pronounced [ˈvita].

The letter beta was derived from the Phoenician letter beth ![]() .

.

The letter Β had the largest number of highly divergent local forms. Besides the standard form (either rounded or pointed, ![]() ), there were forms as varied as

), there were forms as varied as ![]() (Gortyn),

(Gortyn), ![]() and

and ![]() (Thera),

(Thera), ![]() (Argos),

(Argos), ![]() (Melos),

(Melos), ![]() (Corinth),

(Corinth), ![]() (Megara, Byzantium), and

(Megara, Byzantium), and ![]() (Cyclades).

(Cyclades).

Gamma (/ˈɡæmə/;[1] uppercase Γ, lowercase γ; Greek: γάμμα, romanized: gámma) is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop IPA: [ɡ]. In Modern Greek, this letter normally represents a voiced velar fricative IPA: [ɣ], except before either of the two front vowels (/e/, /i/), where it represents a voiced palatal fricative IPA: [ʝ]; while /g/ in foreign words is instead commonly transcribed as γκ).

In the International Phonetic Alphabet and other modern Latin-alphabet based phonetic notations, it represents the voiced velar fricative.

The Greek letter Gamma Γ is a grapheme derived from the Phoenician letter 𐤂 (gīml) which was rotated from the right-to-left script of Canaanite to accommodate the Greek language's writing system of left-to-right. The Canaanite grapheme represented the /g/ phoneme in the Canaanite language, and as such is cognate with gimel ג of the Hebrew alphabet.

Based on its name, the letter has been interpreted as an abstract representation of a camel's neck,[2] but this has been criticized as contrived,[3] and it is more likely that the letter is derived from an Egyptian hieroglyph representing a club or throwing stick.[4]

In Archaic Greece, the shape of gamma was closer to a classical lambda (Λ), while lambda retained the Phoenician L-shape (𐌋).

Letters that arose from the Greek gamma include Etruscan (Old Italic) 𐌂, Roman C and G, Runic kaunan ᚲ, Gothic geuua 𐌲, the Coptic Ⲅ, and the Cyrillic letters Г and Ґ.[5]

The Ancient Greek /g/ phoneme was the voiced velar stop, continuing the reconstructed proto-Indo-European *g, *ǵ.

The modern Greek phoneme represented by gamma is realized either as a voiced palatal fricative (/ʝ/) before a front vowel (/e/, /i/), or as a voiced velar fricative /ɣ/ in all other environments. Both in Ancient and in Modern Greek, before other velar consonants (κ, χ, ξ – that is, k, kh, ks), gamma represents a velar nasal /ŋ/. A double gamma γγ (e.g., άγγελος, "angel") represents the sequence /ŋɡ/ (phonetically varying [ŋɡ~ɡ]) or /ŋɣ/.

Delta (/ˈdɛltə/;[1] uppercase Δ, lowercase δ; Greek: δέλτα, délta, [ˈðelta])[2] is the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 4. It was derived from the Phoenician letter dalet 𐤃.[3] Letters that come from delta include Latin D and Cyrillic Д.

A river delta (originally, the delta of the Nile River) is so named because its shape approximates the triangular uppercase letter delta. Contrary to a popular legend, this use of the word delta was not coined by Herodotus.[4]

In Ancient Greek, delta represented a voiced dental plosive IPA: [d]. In Modern Greek, it represents a voiced dental fricative IPA: [ð], like the "th" in "that" or "this" (while IPA: [d] in foreign words is instead commonly transcribed as ντ). Delta is romanized as d or dh.

The uppercase letter Δ is used to denote:

- Change of any changeable quantity, in mathematics and the sciences (in particular, the difference operator[5][6]); for example, inthe average change of y per unit x (i.e. the change of y over the change of x). Delta is the initial letter of the Greek word διαφορά diaphorá, "difference". (The small Latin letter d is used in much the same way for the notation of derivatives and differentials, which also describe change by infinitesimal amounts.)

- The Laplace operator:

- The discriminant of a polynomial equation, especially the quadratic equation:[7][8]

- The area of a triangle

- The symmetric difference of two sets.

- A macroscopic change in the value of a variable in mathematics or science.

- Uncertainty in a physical variable as seen in the uncertainty principle.

- An interval of possible values for a given quantity.

- Any of the delta particles in particle physics.

- The determinant of the matrix of coefficients of a set of linear equations (see Cramer's rule).

- That an associated locant number represents the location of a covalent bond in an organic compound, the position of which is variant between isomeric forms.

- A simplex, simplicial complex, or convex hull.

- In chemistry, the addition of heat in a reaction.

- In legal shorthand, it represents a defendant.[9]

- In the financial markets, one of the Greeks, describing the rate of change of an option price for a given change in the underlying benchmark.

- A major seventh chord in jazz music notation.

- In genetics, it can stand for a gene deletion (e.g. the CCR5-Δ32, a 32 nucleotide/bp deletion within CCR5).

- The American Dental Association cites it (together with omicron for "odont") as the symbol of dentistry.[10]

- The anonymous signature of James David Forbes.[11]

- Determinacy (having a definite truth-value) in philosophical logic.

- In mathematics, the symbol ≜ (delta over equals) is occasionally used to define a new variable or function.[12]

The lowercase letter δ (or 𝛿) can be used to denote:

- A change in the value of a variable in calculus

- A functional derivative in functional calculus

- The (ε, δ)-definition of limits, in mathematics and more specifically in calculus

- The Kronecker delta in mathematics

- The degree of a vertex (graph theory)

- The Dirac delta function in mathematics

- The transition function in automata

- Deflection in engineering mechanics

- The force of interest in actuarial science

- The chemical shift of nuclear magnetic resonance in chemistry

- The relative electronegativity of different atoms in a molecule, δ− being more electronegative than δ+

- Text requiring deletion in proofreading; the usage is said to date back to classical times

- In some of the manuscripts written by Dr. John Dee, the character of delta is used to represent Dee

- A subunit of the F1 sector of the F-ATPase

- The declination of an object in the equatorial coordinate system of astronomy

- The dividend yield in the Black–Scholes option pricing formula

- Ratios of environmental isotopes, such as 18O/16O and D/1H from water are displayed using delta notation – δ18O and δD, respectively

- The rate of depreciation of the aggregate capital stock of an economy in an exogenous growth model in macroeconomics[13]

- In a system that exhibits electrical reactance, the angle between voltage and current

- Partial charge in chemistry

- The maximum birefringence of a crystal in optical mineralogy.[14]

- An Old Irish voiced dental or alveolar fricative of uncertain articulation, the ancestor of the sound represented by Modern Irish dh

Epsilon (US: /ˈɛpsɪlɒn/,[1] UK: /ɛpˈsaɪlən/;[2] uppercase Ε, lowercase ε or ϵ; Greek: έψιλον) is the fifth letter of the Greek alphabet, corresponding phonetically to a mid front unrounded vowel IPA: [e̞] or IPA: [ɛ̝]. In the system of Greek numerals it also has the value five. It was derived from the Phoenician letter He ![]() . Letters that arose from epsilon include the Roman E, Ë and Ɛ, and Cyrillic Е, È, Ё, Є and Э. The name of the letter was originally εἶ (Ancient Greek: [êː]), but it was later changed to ἒ ψιλόν (e psilon 'simple e') in the Middle Ages to distinguish the letter from the digraph αι, a former diphthong that had come to be pronounced the same as epsilon.

. Letters that arose from epsilon include the Roman E, Ë and Ɛ, and Cyrillic Е, È, Ё, Є and Э. The name of the letter was originally εἶ (Ancient Greek: [êː]), but it was later changed to ἒ ψιλόν (e psilon 'simple e') in the Middle Ages to distinguish the letter from the digraph αι, a former diphthong that had come to be pronounced the same as epsilon.

The uppercase form of epsilon is identical to Latin ⟨E⟩ but has its own code point in Unicode: U+0395 Ε GREEK CAPITAL LETTER EPSILON. The lowercase version has two typographical variants, both inherited from medieval Greek handwriting. One, the most common in modern typography and inherited from medieval minuscule, looks like a reversed number "3" and is encoded U+03B5 ε GREEK SMALL LETTER EPSILON. The other, also known as lunate or uncial epsilon and inherited from earlier uncial writing,[3][4] looks like a semicircle crossed by a horizontal bar: it is encoded U+03F5 ϵ GREEK LUNATE EPSILON SYMBOL. While in normal typography these are just alternative font variants, they may have different meanings as mathematical symbols: computer systems therefore offer distinct encodings for them.[3] In TeX, \epsilon ( ) denotes the lunate form, while \varepsilon ( ) denotes the reversed-3 form. Unicode versions 2.0.0 and onwards use ɛ as the lowercase Greek epsilon letter,[5] but in version 1.0.0, ϵ was used.[6] The lunate or uncial epsilon provided inspiration for the euro sign, €.[7]

There is also a 'Latin epsilon', ⟨ɛ⟩ or "open e", which looks similar to the Greek lowercase epsilon. It is encoded in Unicode as U+025B ɛ LATIN SMALL LETTER OPEN E and U+0190 Ɛ LATIN CAPITAL LETTER OPEN E and is used as an IPA phonetic symbol. This Latin uppercase epsilon, Ɛ, is not to be confused with the Greek uppercase Σ (sigma)

The lunate epsilon, ⟨ϵ⟩, is not to be confused with the set membership symbol ∈. The symbol , first used in set theory and logic by Giuseppe Peano and now used in mathematics in general for set membership ("belongs to"), evolved from the letter epsilon, since the symbol was originally used as an abbreviation for the Latin word est. In addition, mathematicians often read the symbol ∈ as "element of", as in "1 is an element of the natural numbers" for , for example. As late as 1960, ɛ itself was used for set membership, while its negation "does not belong to" (now ∉) was denoted by ε' (epsilon prime).[8] Only gradually did a fully separate, stylized symbol take the place of epsilon in this role. In a related context, Peano also introduced the use of a backwards epsilon, ϶, for the phrase "such that", although the abbreviation s.t. is occasionally used in place of ϶ in informal cardinals.

The letter ⟨Ε⟩ was adopted from the Phoenician letter He (![]() ) when Greeks first adopted alphabetic writing. In archaic Greek writing, its shape is often still identical to that of the Phoenician letter. Like other Greek letters, it could face either leftward or rightward (

) when Greeks first adopted alphabetic writing. In archaic Greek writing, its shape is often still identical to that of the Phoenician letter. Like other Greek letters, it could face either leftward or rightward (![]()

![]() ), depending on the current writing direction, but, just as in Phoenician, the horizontal bars always faced in the direction of writing. Archaic writing often preserves the Phoenician form with a vertical stem extending slightly below the lowest horizontal bar. In the classical era, through the influence of more cursive writing styles, the shape was simplified to the current ⟨E⟩ glyph.[9]

), depending on the current writing direction, but, just as in Phoenician, the horizontal bars always faced in the direction of writing. Archaic writing often preserves the Phoenician form with a vertical stem extending slightly below the lowest horizontal bar. In the classical era, through the influence of more cursive writing styles, the shape was simplified to the current ⟨E⟩ glyph.[9]

While the original pronunciation of the Phoenician letter He was [h], the earliest Greek sound value of Ε was determined by the vowel occurring in the Phoenician letter name, which made it a natural choice for being reinterpreted from a consonant symbol to a vowel symbol denoting an [e] sound.[10] Besides its classical Greek sound value, the short /e/ phoneme, it could initially also be used for other [e]-like sounds. For instance, in early Attic before c. 500 BC, it was used also both for the long, open /ɛː/, and for the long close /eː/. In the former role, it was later replaced in the classic Greek alphabet by Eta (⟨Η⟩), which was taken over from eastern Ionic alphabets, while in the latter role it was replaced by the digraph spelling ΕΙ.

Zeta (UK: /ˈziːtə/, US: /ˈzeɪtə/;[1] uppercase Ζ, lowercase ζ; Ancient Greek: ζῆτα, Demotic Greek: ζήτα, classical [d͡zɛ̌ːta] or [zdɛ̌ːta] zē̂ta; Greek pronunciation: [ˈzita] zíta) is the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 7. It was derived from the Phoenician letter zayin ![]() . Letters that arose from zeta include the Roman Z and Cyrillic З.

. Letters that arose from zeta include the Roman Z and Cyrillic З.

Unlike the other Greek letters, this letter did not take its name from the Phoenician letter from which it was derived; it was given a new name on the pattern of beta, eta and theta.

The word zeta is the ancestor of zed, the name of the Latin letter Z in Commonwealth English. Swedish and many Romance languages (such as Italian and Spanish) do not distinguish between the Greek and Roman forms of the letter; "zeta" is used to refer to the Roman letter Z as well as the Greek letter.

The letter ζ represents the voiced alveolar fricative IPA: [z] in Modern Greek.

The sound represented by zeta in Greek before 400 BC is disputed. See Ancient Greek phonology and Pronunciation of Ancient Greek in teaching.

Most handbooks[who?] agree on attributing to it the pronunciation /zd/ (like Mazda), but some scholars believe that it was an affricate /dz/ (like adze). The modern pronunciation was, in all likelihood, established in the Hellenistic age and may have already been a common practice in Classical Attic; for example, it could count as one or two consonants metrically in Attic drama.[where?]

- PIE *zd becomes ζ in Greek (e.g. *sísdō > ἵζω). Contra: these words are rare and it is therefore more probable that *zd was absorbed by *dz (< *dj, *gj, *j); further, a change from the cluster /zd/ to the affricate /dz/ is typologically more likely[citation needed] than the other way around (which would violate the sonority hierarchy).

- Without [sd] there would be an empty space between [sb] and [sɡ] in the Greek sound system (πρέσβυς, σβέννυμι, φάσγανον), and a voiced affricate [dz] would not have a voiceless correspondent. Contra: a) words with [sb] and [sɡ] are rare, and exceptions in phonological and (even more so) phonotactic patterns are in no way uncommon; b) there was [sd] in ὅσδε, εἰσδέχται etc.; and c) there was in fact a voiceless correspondent in Archaic Greek ([ts] > Attic, Boeotian ττ, Ionic, Doric σσ).

- Persian names with zd and z are transcribed with ζ and σ respectively in Classical Greek (e.g. Artavazda = Ἀρτάβαζος/Ἀρτάοζος ~ Zara(n)ka- = Σαράγγαι. Similarly, the Philistine city Ashdod was transcribed as Ἄζωτος.

- Some inscriptions have -ζ- written for a combination -ς + δ- resulting from separate words, e.g. θεοζοτος for θεος δοτος "god-given".

- Some Attic inscriptions have -σζ- for -σδ- or -ζ-, which is thought to parallel -σστ- for -στ- and therefore to imply a [zd] pronunciation.

- ν disappears before ζ like before σ(σ), στ: e.g. *πλάνζω > πλᾰ́ζω, *σύνζυγος > σύζυγος, *συνστέλλω > σῠστέλλω. Contra: ν may have disappeared before /dz/ if one accepts that it had the allophone [z] in that position like /ts/ had the allophone [s]: cf. Cretan ἴαττα ~ ἀποδίδονσα (Hinge).

- Verbs beginning with ζ have ἐ- in the perfect reduplication like the verbs beginning with στ (e.g. ἔζηκα = ἔσταλται). Contra: a) The most prominent example of a verb beginning with στ has in fact ἑ- < *se- in the perfect reduplication (ἕστηκα); b) the words with /ts/ > σ(σ) also have ἐ-: Homer ἔσσυμαι, -ται, Ion. ἐσσημένῳ.

- Alcman, Sappho, Alcaeus and Theocritus have σδ for Attic-Ionic ζ. Contra: The tradition would not have invented this special digraph for these poets if [zd] was the normal pronunciation in all Greek. Furthermore, this convention is not found in contemporary inscriptions, and the orthography of the manuscripts and papyri is Alexandrine rather than historical. Thus, σδ indicates only a different pronunciation from Hellenistic Greek [z(ː)], i.e. either [zd] or [dz].

- The grammarians Dionysius Thrax[2] and Dionysius of Halicarnassus class ζ with the "double" (διπλᾶ) letters ψ, ξ and analyse it as σ + δ. Contra: The Roman grammarian Verrius Flaccus believed in the opposite sequence, δ + σ (in Velius Longus, De orthogr. 51), and Aristotle says that it was a matter of dispute (Metaph. 993a) (though Aristotle might as well be referring to a [zː] pronunciation). It is even possible that the letter sometimes and for some speakers varied in pronunciation depending upon word position, i.e., like the letter X in English, which is (usually) pronounced [z] initially but [gz] or [ks] elsewhere (cf. Xerxes).

- Some Attic transcriptions of Asia Minor toponyms (βυζζαντειον, αζζειον, etc.) show a -ζζ- for ζ; assuming that Attic value was [zd], it may be an attempt to transcribe a dialectal [dz] pronunciation; the reverse cannot be ruled completely, but a -σδ- transcription would have been more likely in this case. This suggests that different dialects had different pronunciations. (For a similar example in the Slavic languages, cf. Serbo-Croatian (iz)među, Russian между, Polish między, and Czech mezi, "between".)

- The Greek inscriptions almost never write ζ in words like ὅσδε, τούσδε or εἰσδέχται, so there must have been a difference between this sound and the sound of ἵζω, Ἀθήναζε. Contra: a few inscriptions do seem to suggest that ζ was pronounced like σδ; furthermore, all words with written σδ are morphologically transparent, and written σδ may simply be echoing the morphology. (Note, for example, that we write "ads" where the morphology is transparent, and "adze" where it is not, even though the pronunciation is the same.)

- It seems improbable that Greek would invent a special symbol for the bisegmental combination [zd], which could be represented by σδ without any problems. /ds/, on the other hand, would have the same sequence of plosive and sibilant as the double letters of the Ionic alphabet ψ /ps/ and ξ /ks/, thereby avoiding a written plosive at the end of a syllable. Contra: the use of a special symbol for [zd] is no more or no less improbable than the use of ψ for [ps] and ξ for [ks], or, for that matter, the later invention ϛ (stigma) for [st], which happens to be the voiceless counterpart of [zd]. Furthermore, it is not clear that ζ was pronounced [zd] when it was originally invented. Mycenean Greek had a special symbol to denote some sort of affricate or palatal consonant; ζ may have been invented for this sound, which later developed into [zd]. (For a parallel development, note that original palatal Proto-Slavic /tʲ/ developed into /ʃt/ in Old Church Slavonic, with similar developments having led to combinations such as зд and жд being quite common in Russian.)

- Boeotian, Elean, Laconian and Cretan δδ are more easily explained as a direct development from *dz than through an intermediary *zd. Contra: a) the sound development dz > dd is improbable (Mendez Dosuna); b) ν has disappeared before ζ > δδ in Laconian πλαδδιῆν (Aristoph., Lys. 171, 990) and Boeotian σαλπίδδω (Sch. Lond. in Dion. Thrax 493), which suggests that these dialects have had a phase of metathesis (Teodorsson).

- Greek in South Italy has preserved [dz] until modern times. Contra: a) this may be a later development from [zd] or [z] under the influence of Italian; b) even if it is derived from an ancient [dz], it may be a dialectal pronunciation.

- Vulgar Latin inscriptions use the Greek letter Z for indigenous affricates (e.g. zeta = diaeta), and the Greek ζ is continued by a Romance affricate in the ending -ίζω > Italian. -eggiare, French -oyer. Italian, similarly, has consistently used Z for [dz] and [ts] (Lat. prandium > It. pranzo, "lunch"). Contra: whether the pronunciation of ζ was [dz], [zd] or [zː], di would probably still have been the closest native Latin sound; furthermore, the inscriptions are centuries later than the time for which [zd] is assumed.

- σδ is attested only in the lyric poetry of the Greek isle of Lesbos and the city-state of Sparta during the Archaic Age and in Bucolic poetry from the Hellenistic Age. Most scholars would take this as an indication that the [zd]-pronunciation existed in the dialects of these authors.

- The transcriptions from Persian by Xenophon and testimony by grammarians support the pronunciation [zd] in Classical Attic.

- [z(ː)] is attested from c. 350 BC in Attic inscriptions, and was the probable value in Koine.

- [dʒ] or [dz] may have existed in some other dialects in parallel.

Zeta has the numerical value 7 rather than 6 because the letter digamma (ϝ, also called 'stigma' as a Greek numeral) was originally in the sixth position in the alphabet.

Eta (/ˈiːtə, ˈeɪtə/ EE-tə, AY-tə;[1] uppercase Η, lowercase η; Ancient Greek: ἦτα ē̂ta [ɛ̂ːta] or Greek: ήτα ita [ˈita]) is the seventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the close front unrounded vowel, [i]. Originally denoting the voiceless glottal fricative, [h], in most dialects of Ancient Greek, its sound value in the classical Attic dialect was a long open-mid front unrounded vowel, [ɛː], which was raised to [i] in Hellenistic Greek, a process known as iotacism or itacism.

In the ancient Attic number system (Herodianic or acrophonic numbers), the number 100 was represented by "Η", because it was the initial of ΗΕΚΑΤΟΝ, the ancient spelling of ἑκατόν = "one hundred". In the later system of (Classical) Greek numerals eta represents 8.

Eta was derived from the Phoenician letter heth ![]() . Letters that arose from eta include the Latin H and the Cyrillic letters И and Й.

. Letters that arose from eta include the Latin H and the Cyrillic letters И and Й.

The letter shape 'H' was originally used in most Greek dialects to represent the voiceless glottal fricative, [h]. In this function, it was borrowed in the 8th century BC by the Etruscan and other Old Italic alphabets, which were based on the Euboean form of the Greek alphabet. This also gave rise to the Latin alphabet with its letter H.

Other regional variants of the Greek alphabet (epichoric alphabets), in dialects that still preserved the sound [h], employed various glyph shapes for consonantal heta side by side with the new vocalic eta for some time. In the southern Italian colonies of Heracleia and Tarentum, the letter shape was reduced to a "half-heta" lacking the right vertical stem (Ͱ). From this sign later developed the sign for rough breathing or spiritus asper, which brought back the marking of the [h] sound into the standardized post-classical (polytonic) orthography.[2] Dionysius Thrax in the second century BC records that the letter name was still pronounced heta (ἥτα), correctly explaining this irregularity by stating "in the old days the letter Η served to stand for the rough breathing, as it still does with the Romans."[3]

In the East Ionic dialect, however, the sound [h] disappeared by the sixth century BC, and the letter was re-used initially to represent a development of a long open front unrounded vowel, [aː], which later merged in East Ionic with the long open-mid front unrounded vowel, [ɛː] instead.[4] In 403 BC, Athens took over the Ionian spelling system and with it the vocalic use of H (even though it still also had the [h] sound itself at that time). This later became the standard orthography in all of Greece.

During the time of post-classical Koiné Greek, the [ɛː] sound represented by eta was raised and merged with several other formerly distinct vowels, a phenomenon called iotacism or itacism, after the new pronunciation of the letter name as ita instead of eta.

Itacism is continued into Modern Greek, where the letter name is pronounced [ˈita] and represents the close front unrounded vowel, [i]. It shares this function with several other letters (ι, υ) and digraphs (ει, οι), which are all pronounced alike.

In Modern Greek, due to iotacism, the letter (pronounced [ˈita]) represents a close front unrounded vowel, [i]. In Classical Greek, it represented the long open-mid front unrounded vowel, [ɛː].

The uppercase letter Η is used as a symbol in textual criticism for the Alexandrian text-type (from Hesychius, its once-supposed editor).

In chemistry, the letter H as symbol of enthalpy sometimes is said to be a Greek eta, but since enthalpy comes from ἐνθάλπος, which begins in a smooth breathing and epsilon, it is more likely a Latin H for 'heat'.

In information theory the uppercase Greek letter Η is used to represent the concept of entropy of a discrete random variable.

The lowercase letter η is used as a symbol in:

- Thermodynamics, the efficiency of a Carnot heat engine, or packing fraction.

- Aeronautics, the propulsive efficiency, or percentage of chemical energy converted to kinetic energy.

- Chemistry, the hapticity, or the number of atoms of a ligand attached to one coordination site of the metal in a coordination compound. For example, an allyl group can coordinate to palladium in the η¹ mode (only one atom of an allyl group attached to palladium) or the η³ mode (3 atoms attached to palladium).

- Optics, the electromagnetic impedance of a medium, or the quantum efficiency of detectors.

- Particle physics, to represent the η mesons.

- Experimental particle physics, η stands for pseudorapidity.

- Cosmology, η represents conformal time; dt = adη.

- Cosmology, baryon–photon ratio.

- Relativity and Quantum field theory (physics), η (with two subscripts) represents the metric tensor of Minkowski space (flat spacetime).

- Statistics, η2 is the "partial regression coefficient". η is the symbol for the linear predictor of a generalized linear model, and can also be used to denote the median of a population, or thresholding parameter in Sparse Partial Least Squares regression.

- Economics, η is the elasticity.

- Astronomy, the seventh-brightest (usually) star in a constellation. See Bayer designation.

- Mathematics, η-reduction in lambda calculus.

- Mathematics, the Dirichlet eta function, Dedekind eta function, and Weierstrass eta function.

- In category theory, the unit of an adjunction or monad is usually denoted η.

- Biology, a DNA polymerase found in higher eukaryotes and implicated in Translesion Synthesis.

- Neural network backpropagation, and stochastic gradient descent more generally, η stands for the learning rate.

- Telecommunications, η stands for efficiency

- Electronics, η stands for the ideality factor of a bipolar transistor, and has a value close to 1.000. It appears in contexts where the transistor is used as a temperature sensing device, e.g. the thermal "diode" transistor that is embedded within a computer's microprocessor.

- Power electronics, η stands for the efficiency of a power supply, defined as the output power divided by the input power.

- Atmospheric science, η represents absolute atmospheric vorticity.

- Rheology, η represents viscosity.

- Oceanography, η is the measurement (usually in metres) of sea-level height above or below the mean sea-level at that same location.

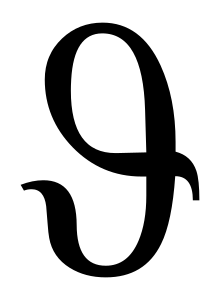

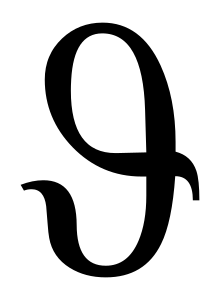

Theta (UK: /ˈθiːtə/, US: /ˈθeɪtə/; uppercase Θ or ϴ; lowercase θ[note 1] or ϑ; Ancient Greek: θῆτα thē̂ta [tʰɛ̂ːta]; Modern: θήτα thī́ta [ˈθita]) is the eighth letter of the Greek alphabet, derived from the Phoenician letter Teth ![]() . In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 9.

. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 9.

In Ancient Greek, θ represented the aspirated voiceless dental plosive IPA: [t̪ʰ], but in Modern Greek it represents the voiceless dental fricative IPA: [θ].

In its archaic form, θ was written as a cross within a circle (as in the Etruscan ![]() or

or ![]() ), and later, as a line or point in circle (

), and later, as a line or point in circle (![]() or

or ![]() ).

).

The cursive form ϑ was retained by Unicode as U+03D1 ϑ GREEK THETA SYMBOL, separate from U+03B8 θ GREEK SMALL LETTER THETA. (There is also U+03F4 ϴ GREEK CAPITAL THETA SYMBOL). For the purpose of writing Greek text, the two can be font variants of a single character, but θ and ϑ are also used as distinct symbols in technical and mathematical contexts. Extensive lists of examples follow below at Mathematics and Science. U+03D1 ϑ GREEK THETA SYMBOL (script theta) is also common in biblical and theological usage e.g. πρόϑεσις (prothesis) instead of πρόθεσις (means placing in public or laying out a corpse).

Theta (UK: /ˈθiːtə/, US: /ˈθeɪtə/; uppercase Θ or ϴ; lowercase θ[note 1] or ϑ; Ancient Greek: θῆτα thē̂ta [tʰɛ̂ːta]; Modern: θήτα thī́ta [ˈθita]) is the eighth letter of the Greek alphabet, derived from the Phoenician letter Teth ![]() . In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 9.

. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 9.

In Ancient Greek, θ represented the aspirated voiceless dental plosive IPA: [t̪ʰ], but in Modern Greek it represents the voiceless dental fricative IPA: [θ].

In its archaic form, θ was written as a cross within a circle (as in the Etruscan ![]() or

or ![]() ), and later, as a line or point in circle (

), and later, as a line or point in circle (![]() or

or ![]() ).

).

The cursive form ϑ was retained by Unicode as U+03D1 ϑ GREEK THETA SYMBOL, separate from U+03B8 θ GREEK SMALL LETTER THETA. (There is also U+03F4 ϴ GREEK CAPITAL THETA SYMBOL). For the purpose of writing Greek text, the two can be font variants of a single character, but θ and ϑ are also used as distinct symbols in technical and mathematical contexts. Extensive lists of examples follow below at Mathematics and Science. U+03D1 ϑ GREEK THETA SYMBOL (script theta) is also common in biblical and theological usage e.g. πρόϑεσις (prothesis) instead of πρόθεσις (means placing in public or laying out a corpse).

Iota (/aɪˈoʊtə/;[1] uppercase Ι, lowercase ι; Greek: ιώτα) is the ninth letter of the Greek alphabet. It was derived from the Phoenician letter Yodh.[2] Letters that arose from this letter include the Latin I and J, the Cyrillic І (І, і), Yi (Ї, ї), and Je (Ј, ј), and iotated letters (e.g. Yu (Ю, ю)). In the system of Greek numerals, iota has a value of 10.[3]

Iota represents the close front unrounded vowel IPA: [i]. In early forms of ancient Greek, it occurred in both long [iː] and short [i] versions, but this distinction was lost in Koine Greek.[4] Iota participated as the second element in falling diphthongs, with both long and short vowels as the first element. Where the first element was long, the iota was lost in pronunciation at an early date, and was written in polytonic orthography as iota subscript, in other words as a very small ι under the main vowel. Examples include ᾼ ᾳ ῌ ῃ ῼ ῳ. The former diphthongs became digraphs for simple vowels in Koine Greek.[4]

The word is used in a common English phrase, "not one iota", meaning "not the slightest amount". This refers to iota, the smallest letter, or possibly yodh, י, the smallest letter in the Hebrew alphabet.[citation needed] The English word jot derives from iota.[5] The German, Polish, Portuguese, and Spanish name for the letter J (Jot / jota) is derived from iota.

Kappa (/ˈkæpə/;[1] uppercase Κ, lowercase κ or cursive ϰ; Greek: κάππα, káppa) is the tenth letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the voiceless velar plosive IPA: [k] sound in Ancient and Modern Greek. In the system of Greek numerals, Kʹ has a value of 20. It was derived from the Phoenician letter kaph ![]() . Letters that arose from kappa include the Roman K and Cyrillic К. The uppercase form is identical to the Latin K.

. Letters that arose from kappa include the Roman K and Cyrillic К. The uppercase form is identical to the Latin K.

Greek proper names and placenames containing kappa are often written in English with "c" due to the Romans' transliterations into the Latin alphabet: Constantinople, Corinth, Crete. All formal modern romanizations of Greek now use the letter "k", however.[citation needed]

The cursive form ϰ is generally a simple font variant of lower-case kappa, but it is encoded separately in Unicode for occasions where it is used as a separate symbol in math and science. In mathematics, the kappa curve is named after this letter; the tangents of this curve were first calculated by Isaac Barrow in the 17th century.

- Mathematics and statistics

- In graph theory, the connectivity of a graph is given by κ.

- In differential geometry, the curvature of a curve is given by κ.

- In linear algebra, the condition number of a matrix is given by κ.

- Kappa statistics such as Cohen's kappa and Fleiss' kappa are methods for calculating inter-rater reliability.

- Physics

- In cosmology, the Einstein gravitational constant is denoted by κ.

- In physics, the torsional constant of an oscillator is given by κ.

- In physics, the coupling coefficient in magnetostatics is represented by κ.

- In physics, the dielectric coefficient is represented by κ.

- In fluid dynamics, the von Kármán constant is represented by κ.

- In thermodynamics, the compressibility of a compound is given by κ.

- Engineering

- In structural engineering, κ is the ratio of the smaller factored moment to the larger factored moment and is used to calculate the critical elastic moment of an unbraced steel member.

- In electrical engineering, κ is the multiplication factor, a function of the R/X ratio of the equivalent power system network, which is used in calculating the peak short-circuit current of a system fault. κ is also used to denote conductivity, the reciprocal of resistivity, rho.

- Biology and biomedical science

- In biology, kappa and kappa prime are important nucleotide motifs for a tertiary interaction of group II introns.

- In biology, kappa designates a subtype of an antibody component.

- In pharmacology, kappa represents a type of opioid receptor.

- Psychology and psychiatry

- In psychology and psychiatry, kappa represents a measure of diagnostic reliability.

- Economics

- In macroeconomics, kappa represents the capital-utilization rate.[2]

- History

- In textual criticism, the Byzantine text-type (from Κοινη, Koine, the common text).

- Mathematics and statistics

- In set theory, kappa is often used to denote an ordinal that is also a cardinal.

- Chemistry

- In chemistry, kappa is used to denote the denticity of the compound.

- In pulping, the kappa number represents the amount of an oxidizing agent required for bleaching a pulp.

Lambda (/ˈlæmdə/;[1] uppercase Λ, lowercase λ; Greek: λάμ(β)δα, lám(b)da) is the eleventh letter of the Greek alphabet, representing the voiced alveolar lateral approximant IPA: [l]. In the system of Greek numerals, lambda has a value of 30. Lambda is derived from the Phoenician Lamed. Lambda gave rise to the Latin L and the Cyrillic El (Л). The ancient grammarians and dramatists give evidence to the pronunciation as [laːbdaː] (λάβδα) in Classical Greek times.[2] In Modern Greek, the name of the letter, Λάμδα, is pronounced [ˈlam.ða].

In early Greek alphabets, the shape and orientation of lambda varied.[3] Most variants consisted of two straight strokes, one longer than the other, connected at their ends. The angle might be in the upper-left, lower-left ("Western" alphabets) or top ("Eastern" alphabets). Other variants had a vertical line with a horizontal or sloped stroke running to the right. With the general adoption of the Ionic alphabet, Greek settled on an angle at the top; the Romans put the angle at the lower-left.

Examples of the symbolic use of uppercase lambda include:

- The lambda particle is a type of subatomic particle in subatomic particle physics.

- Lambda is the set of logical axioms in the axiomatic method of logical deduction in first-order logic.

- There is a poetical allusion to the use of Lambda as a shield blazon by the Spartans.[citation needed][5]

- Lambda is the von Mangoldt function in mathematical number theory.

- Lambda denotes the de Bruijn–Newman constant which is closely connected with Riemann's hypothesis.

- In statistics, lambda is used for the likelihood ratio.

- In statistics, Wilks's lambda is used in multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA analysis) to compare group means on a combination of dependent variables.

- In the spectral decomposition of matrices, lambda indicates the diagonal matrix of the eigenvalues of the matrix.

- In computer science, lambda is the time window over which a process is observed for determining the working memory set for a digital computer's virtual memory management.

- In astrophysics, lambda represents the likelihood that a small body will encounter a planet or a dwarf planet leading to a deflection of a significant magnitude. An object with a large value of lambda is expected to have cleared its neighbourhood, satisfying the current definition of a planet.

- In crystal optics, lambda is used to represent a lattice period.

- In NATO military operations, a chevron (a heraldic symbol which looks like a capital letter lambda or inverted V) is painted on the vehicles of this military alliance for identification.

- In electrochemistry, lambda denotes the "equivalent conductance" of an electrolyte solution.

- In cosmology, lambda is the symbol for the cosmological constant, a term added to some dynamical equations to account for the accelerating expansion of the universe.

- In optics, lambda denotes the grating pitch of a Bragg reflector. Also in optics, it denotes wavelength of light.

- In politics, the lambda is the symbol of Identitarianism, a white nationalist movement that originated in France before spreading out to the rest of Europe and later on to North America, Australia and New Zealand. The Identitarian lambda represents the Battle of Thermopylae.

- Lambda indicates the wavelength of any wave, especially in physics, electrical engineering, and mathematics.[6]

- In evolutionary algorithms, λ indicates the number of offspring that would be generated from μ current population in each generation. The terms μ and λ are originated from Evolution strategy notation.

- Lambda indicates the radioactivity decay constant in nuclear physics and radioactivity. This constant is very simply related (by a multiplicative constant) to the half-life of any radioactive material.

- In probability theory, lambda represents the density of occurrences within a time interval, as modelled by the Poisson distribution.

- In mathematical logic and computer science, lambda is used to introduce anonymous functions expressed with the concepts of lambda calculus.

- Lambda indicates an eigenvalue in the mathematics of linear algebra.

- In the physics of particles, lambda indicates the thermal de Broglie wavelength

- In the physics of electric fields, lambda sometimes indicates the linear charge density of a uniform line of electric charge (measured in coulombs per meter).

- Lambda denotes a Lagrange multiplier in multi-dimensional calculus.

- In solid-state electronics, lambda indicates the channel length modulation parameter of a MOSFET.

- In ecology, lambda denotes the long-term intrinsic growth rate of a population. This value is often calculated as the dominant eigenvalue of the age/size class matrix.

- In formal language theory and in computer science, lambda denotes the empty string.

- Lambda is a nonstandard symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet for the voiced alveolar lateral affricate [dɮ].

- Lambda denotes the Lebesgue measure in mathematical set theory.

- The Goodman and Kruskal's lambda in statistics indicates the proportional reduction in error when one variable's values are used to predict the values of another variable.

- Lambda denotes the oxygen sensor in a vehicle that measures the air-to-fuel ratio in the exhaust gases of an internal-combustion engine.

- A Lambda 4S solid-fuel rocket was used to launch Japan's first orbital satellite in 1970.[7]

- Lambda denotes the failure rate of devices and systems in reliability theory, and it is measured in failure events per hour. Numerically, this lambda is also the reciprocal of the mean time between failures.

- In criminology, lambda denotes an individual's frequency of offences.

- In electrochemistry, lambda also denotes the ionic conductance of a given ion (the composition of the ion is generally shown as a subscript to the lambda character).

- In neurobiology, lambda denotes the length constant (or exponential rate of decay) of the electric potential across the cell membrane along a length of a nerve cell's axon.

- In the science and technology of heat transfer, lambda denotes the heat of vaporization per mole of material (a.k.a. its "latent heat").[8]

- In the technology and science of celestial navigation, lambda denotes the longitude as opposed to the Roman letter "L", which denotes the latitude.

- A block style lambda is used as a recurring symbol in the Valve computer game series Half-Life,[9] referring to the Lambda Complex of the fictional Black Mesa Research Facility, as well as making appearances in the sequel Half-Life 2, and its subsequent prequel Half-Life: Alyx as an in universe symbol of resistance.[10]

- In 1970, a lowercase lambda was chosen by Tom Doerr as the symbol of the New York chapter of the Gay Activists Alliance.[11][12] The lambda symbol became associated with Gay Liberation[13][14] and recognized as an LGBT symbol for some time afterwards, being used as such by the International Gay Rights Congress in Edinburgh.[15]

"μ" is conventionally used to denote certain things; however, any Greek letter or other symbol may be used freely as a variable name.

- a measure in measure theory

- minimalization in computability theory and Recursion theory

- the integrating factor in ordinary differential equations

- the degree of membership in a fuzzy set

- the Möbius function in number theory

- the population mean or expected value in probability and statistics

- the Ramanujan–Soldner constant

In classical physics and engineering:

- the coefficient of friction (also used in aviation as braking coefficient (see Braking action))

- reduced mass in the two-body problem

- Standard gravitational parameter in celestial mechanics

- linear density, or mass per unit length, in strings and other one-dimensional objects

- permeability in electromagnetism

- the magnetic dipole moment of a current-carrying coil

- dynamic viscosity in fluid mechanics

- the amplification factor or voltage gain of a triode vacuum tube[6]

- the electrical mobility of a charged particle

- the rotor advance ratio, the ratio of aircraft airspeed to rotor-tip speed in rotorcraft[7][8]

- the pore water pressure in saturated soil

In particle physics:

- the elementary particles called the muon and antimuon

- the proton-to-electron mass ratio

In thermodynamics:

- the chemical potential of a system or component of a system

- μ, population size from which in each generation λ offspring will generate (the terms μ and λ originate from evolution strategy notation)

In type theory:

- Used to introduce a recursive data type. For example, is the type of lists with elements of type (a type variable): a sum of unit, representing nil, with a pair of a and another (represented by ). In this notation, is a binding form, where the variable () introduced by is bound within the following term () to the term itself. Via substitution and arithmetic, the type expands to , an infinite sum of ever-increasing products of (that is, a is any -tuple of values of type for any ). Another way to express the same type is .

In chemistry:

- the prefix given in IUPAC nomenclature for a bridging ligand

In biology:

- the mutation rate in population genetics

- A class of Immunoglobulin heavy chain that defines IgM type Antibodies

In pharmacology:

- an important opiate receptor

- Standard gravitational parameter of a celestial body, the product of the gravitational constant G and the mass M

- planetary discriminant, represents an experimental measure of the actual degree of cleanliness of the orbital zone, a criterion for defining a planet. The value of μ is calculated by dividing the mass of the candidate body by the total mass of the other objects that share its orbital zone.

- Mu chord

- Electronic musician Mike Paradinas runs the label Planet Mu which utilizes the letter as its logo, and releases music under the pseudonym μ-Ziq, pronounced "music"

- Used as the name of the school idol group μ's, pronounced "muse", consisting of nine singing idols in the anime Love Live! School Idol Project

- Official fandom name of Kpop group f(x), appearing as either MeU or 'μ'

- Hip-hop artist Muonboy has taken inspiration from the particle for his stage name and his first EP named Mu uses the letter as its title.

The Olympus Corporation manufactures a series of digital cameras called Olympus μ [mju:][9] (known as Olympus Stylus in North America).

In phonology:

In syntax:

- μP (mu phrase) can be used as the name for a functional projection.[10]

In Celtic linguistics:

- /μ/ can represent an Old Irish nasalized labial fricative of uncertain articulation, the ancestor of the sound represented by Modern Irish mh.

Comments

Post a Comment

No Comment